Should China retaliate in this trade war?

Sudden and erratic announcements of extensive US tariffs on Chinese goods, which at the time of writing stand at 145%, have sent shockwaves through both the Chinese and global economies. China’s current reciprocal tariffs stand at 125%. The long simmering US-China trade war has now reached a boiling point, leaving many wondering: is China’s firm retaliation against Trump’s tariff the right response?

In this article, CEIBS Professor of Accounting Dingbo Xu shares his analysis and perspective on this urgent issue. This is a translation with minor modifications of an article originally posted on Professor Xu’s WeChat account in Chinese on April 9 (Beijing Time).

By Dingbo Xu

When wondering how exactly China should respond to the rapidly escalating and unpredictable tariff war initiated by US President Donald Trump, game theory can provide us with an instructive perspective. While I no longer specialise in economics research myself, one of my professors during my doctoral programme was Alvin Roth, one of the world’s foremost game theorists. Roth won the 2012 Nobel Prize in Economics, and I took his courses on "Game Theory" and "Bargaining Theory."

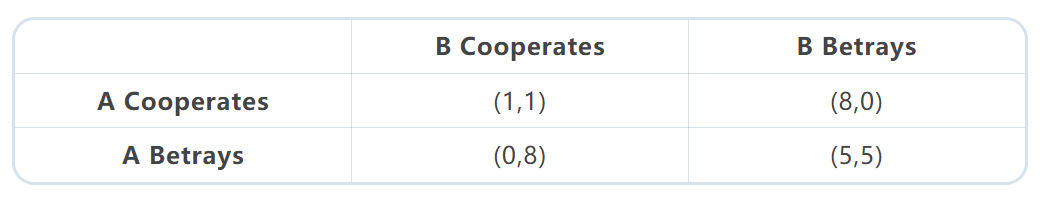

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is the most famous example of non-zero-sum game in game theory. It illustrates that in a strategic interaction, in which individuals face a choice between cooperation and betrayal, the optimal choice for an individual may not align with the group’s best interest. That means when both parties pursue the best choices for them personally as individuals, the result is the worst outcome for the group.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma was first proposed by American mathematicians Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher in 1950. It presents a seemingly simple scenario, outlined below:

- The police arrest two suspects, A and B, who engaged in a crime together; but the police lack sufficient evidence to convict them.

- A and B are held separately and offered the same deal:

- If both remain silent, both serve one year (1, 1).

- If both confess, each gets five years in prison (5, 5).

- If one confesses while the other stays silent, the confessor goes free while the silent one gets eight years (0, 8) or (8, 0).

This is also summarised in the table below:

The optimal outcome for both is clearly mutual cooperation – both remaining silent and each serving one year (1, 1). However, in reality, each prisoner will likely fear that the other will betray them, meaning that a likely response is for both prisoners to confess, leading to a worse outcome (5, 5).

Following on from this, many people in China, including some prominent economists, argue that China should make concessions in this US-initiated trade war, for two main reasons:

- They hope to avoid the worst-case scenario (5, 5) for both sides.

- They believe China’s concessions could lead to more lenient treatment from the US.

In my view, this is the incorrect approach, for three reasons which I will outline below.

1. Three Key Considerations in Applying the Prisoner’s Dilemma to the US-China Trade War

- I) Will China’s concessions lead to US leniency?

My judgment is no. The prevailing US narrative is that China has reaped enormous benefits from globalisation over the past 40 years, while the US has suffered losses in parallel. In fact, this view is one of rare bipartisan consensuses in Washington; it also enjoys widespread support from US academia and the general public. On the surface, data does seem to support this: according to IMF estimations, from 2007 to 2024, China’s real per capita GDP grew by 196%, while the US grew by only 25%. Chinese customs data also show that, while running a trade deficit in services, China’s trade surplus in goods increased in the latest seven years, peaking at 992 billion USD in 2024.

However, while globalisation has been crucial to China’s rapid economic growth, other factors are equally important:

- The diligence, innovation, and work ethic of the Chinese population

- High savings rates

- Dramatic improvements in public health and education over the past 70 years

- Political stability

- Reform and opening-up policies

Trade deficits have become a devil in political discussions around the world. In fact, trade deficits are merely the necessary “foreign savings” to fill the gap between an economy’s domestic savings and investment. Savings rate difference is the major factor affecting trade balances. In 2023, the US gross savings rate was only 17.4%, while for China the number was 44.3%. The huge US federal government budget deficit is the most important driver for the low US savings rate. The past demographic state and insufficient social security are the main reasons that can explain China’s high savings rate.

Given China’s rapid economic growth and persistent trade surpluses, US-China trade tensions - and broader geopolitical tensions – were probably unavoidable, and given current US attitudes, strategic patience and concessions will now have little effect. That said, I also do not advocate provoking unnecessary conflict.

- II) Should major powers adopt different strategies from smaller or weaker nations?

My answer is yes. In this trade war, countries like Vietnam, for example, or certain countries in South America and Europe, have little choice but to yield to US pressure and hope for leniency. This effectively places themselves at the mercy of the American government.

But a country of similar or greater strength, like China, should leverage credible threats and countermeasures to try and force the other side to change its behaviour and seek cooperation. This is the response most likely to achieve the optimal outcome for both sides.

- III) Is China now on equal (or even stronger) footing with the U.S.?

Again, my answer is yes. The US has far less influence on the global economy than many assume. Consider the factors below:

- According to World Bank data, the US share of global exports has fallen from 15.51% in 1970 to 9.8% in 2023, while China’s has risen from 0.59% to 11.28%. China is now the largest trading partner for the majority of countries.

- Only 6% of China’s imports come from the US, while 15% of its exports go directly to the US. The US is no longer China’s top export market. China’s top trading partner is ASEAN.

- In many sectors, the US still depends on Chinese imports, making a full-decoupling impossible.

Even more importantly, GDP based on purchasing power parity (PPP) reflects the actual economic strength of each nation more accurately. The US share of global GDP (PPP) has fallen from 21.58% in 1980 to 15.05% in 2023. China’s has risen from 2.05% to 18.75% over the same period.

The US does hold one card: its massive consumer market. However, from 1970 to 2023, the US share of global imports has fallen from 14.49% to 12.73% while China’s has risen from 0.57% to 10.34%. The US is still the largest global importer. But as China’s economy recovers and domestic consumption grows, these dynamics will shift.

2) The Trade War Will Hurt the US More than its Partners

History is a mirror. In response to the 1929 Wall Street crash, President Herbert Hoover implemented three key policies:

- Mass deportation of undocumented immigrants

- Sharp income tax cuts

- Higher trade tariffs

By 1932, US tariffs had peaked at 59.1%, the second-highest in history after the record of 61.7% in 1830. Instead of saving the economy, these policies helped to push the US economy into the Great Depression: unemployment hit 25%, and American GDP shrank by one-third.

Today, Trump is repeating the same three policies - and many in the US are sounding the alarm.

3) Why Did Japan Yield in the 1980s Trade War?

While looking to the past for reference, many see parallels in Japan’s economic rise in the 1980s. Why did Japan concede during the US-Japan trade conflict in that decade? In asking this question, we sometimes lost sight of the simple fact that China today is not Japan in 1985.

Japan at that time lacked China’s economic fundamentals. Consider the reasons below:

- China has a vastly larger domestic market spanning from rich coastal cities to inland regions.

- China has built a global economic network through the Belt and Road Initiative.

- China’s manufacturing system is the world’s largest and most comprehensive one, which makes China’s economy much less vulnerable to the American bully than Japan in the 1980s.

- Unlike Japan, China is not politically or militarily dependent on the US.

We could learn a lesson from Japan’s concessions in the Plaza Accord in response to US pressure: the 30 years of stagnation that followed. This is a fate China must avoid.

4) Short-Term Pain, Long-Term Optimism

A few years ago, I said my view on Sino-US relations was:

- Short-term optimistic

- Medium-term pessimistic

- Long-term optimistic

We are now in the medium-term pessimism phase. The trade war’s impact on global trade and financial markets will be severe, but I believe this phase won’t last long.

My long-term optimism remains, for the following key reasons:

- Trump’s motives are commercial, not ideological - he is a businessman using extreme pressure to force concessions from his negotiating partners.

- China’s aging population will reduce its savings rate and the Chinese government has taken measures to boost domestic consumption.

- China will strive to build a global trade system that is no longer dominated by the US; more countries are now willing to cooperate with China.

- Trade tensions thus far have not stopped China’s rise – this is evidenced by achievements like the Tiangong Space Station, BeiDou Navigation Satellite System, remarkable development in high-speed rail, and AI developments like DeepSeek.

5) Globalisation Remains the Right Path

I have long argued that globalisation is the right path for humanity. Domestic challenges faced by each individual nation could drive us apart, but the global challenges and uncertainties jointly faced by all nations will “reunite” the world. Both economic rationality and history support this conviction. Of course, to convince the sceptics of globalization will need much more than this one short article.

We should remain confident and united in order to weather this storm. If we avoid making strategic mistakes, I am confident that lives around the world will be much better in a few short years.

Dingbo Xu is Essilor Chair Professor of Accounting and Associate Dean at CEIBS. His research focuses on mechanism design, the role of accounting information disclosure on management decision-making, performance evaluation and incentive. His research has been published in several academic journals and books.